Lecture 10 - CI, CD, and the Development Process

Lectrue 10 - CI, CD, and the Development Process#

News and Housekeeping#

- Check-in 3 will be starting up this week. Due to holidays and such, availability may be limited during some weeks in November — please expect to come in earlier and talk about what you’ve built and learned so far this semester.

- I owe some of your participation points; I need to do better about asking for your names if I don’t know them yet. If you have asked one or both of your questions already and don’t see points in Learning Suite for it yet, please come talk to me after class or shoot me a slack message.

- Please make sure you are tracking your attendance in Learning Suite. Some of you have not recorded any attendance yet.

- Because Check-In 3 is how I assess the “App Progress” grade, it is mandatory. You have a full month to do it. Because I have to submit grades after Check-In 3 closes, not coming to check in means 65% of your grade can’t be submitted. I don’t want to have to do that.

Lecture 9 Follow-Up#

Anything we want to revisit for frontend before we talk about CI / CD? We ran out of time last time. I’m happy to do another demo of some UI principles if that’s useful to y’all.

Continuous Integration#

CI is short for Continuous Integration. There are a couple facets to this:

- Branch-based development

- Fast turnaround time on if the code on a branch is working properly (builds, formats, tests)

- Code reviews

- Incremental changes rather than massive merges

Branch-based Development#

Without a good reason otherwise, you should be using git to manage your code. Git gives you a lot of features, many of which only start to make sense when collaborating. One of these is branch-based development.

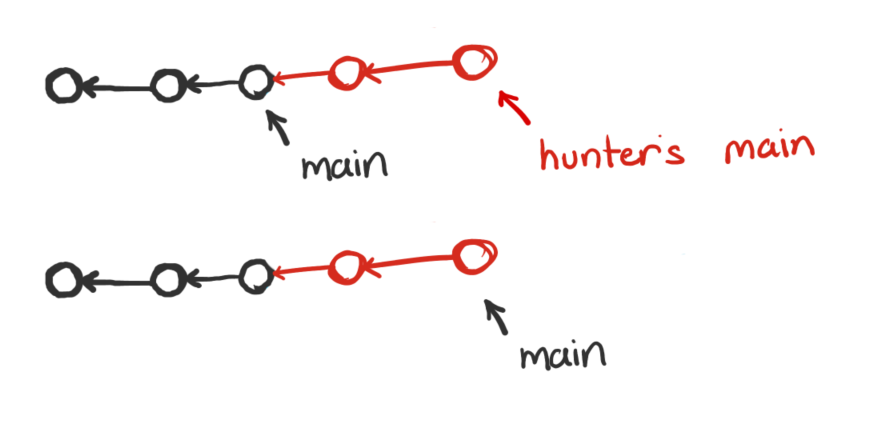

Git is a linked list, or a block chain. Each node in the list has a parent, and

can only have one parent. Each branch can also only have one HEAD node, the

commit that that branch name refers to. An easy merge just means updating the

main branch label to point at a new commit:

This can be a little tricky to keep track of with multiple people however, because each person has their own clone:

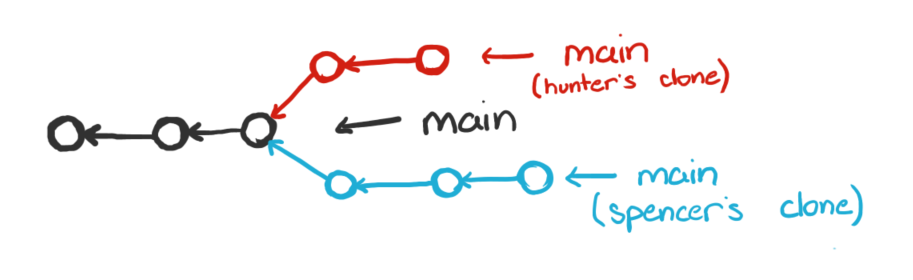

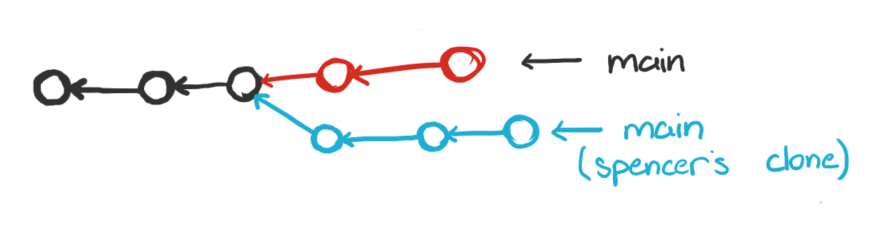

If I push my changes first, we get in a state like this:

Now Spencer has to resolve this problem because the main that he’s trying to push to no longer matches the root commit he’s thinks it does. In that case, Spencer either needs to do a merge commit (take Hunter’s changes into account), or a rebase (make his commits point at the new head commit of the main branch).

Either way, the commits on Spencer’s branch need to be updated with new parents before we can merge.

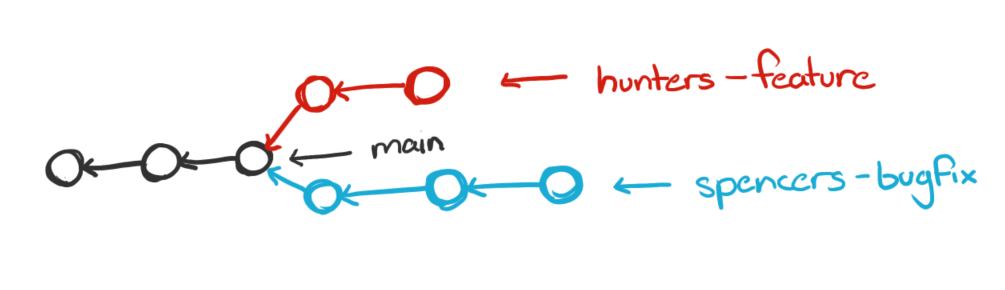

Branches make this a bit less painful, because instead of needing to manage multiple copies of one name, we have specific names for things:

Then when I’m ready to be done with my feature and have it on main, I can

just:

git checkout maingit merge hunters-featureIf main has already had commits since then, it will rewrite the commits being added to have the proper parents for me.

Merge Conflicts#

What happens if we both edit a file? Well, then we get merge conflicts, and won’t be able to merge the code without fixing the conflicts.

(We are going to do a demo here in class. Feel free to add your name after my name, and create a pull request)

This is what a merge conflict looks like:

# Visitor List

<<<<<<< HEAD

- # Hunter Henrichsen- Spencer Bartholomew > > > > > > > add-spencer-to-visitors- Chris CrittendenThe equals signs are a divider, and the greater/less than signs are markers for the head branch and the current branch being merged changes. Most of the time, these aren’t hard to resolve; just a renamed variable or other similar issue making it hard for git to tell where to put the new changes.

Git as a Source of Truth#

Requirements change over time, so maintaining a clear history of what changed and why become useful down the road. Compare these two commit messages:

Change the injector to no longer inject nulls

No longer inject nulls

Throw an error to prevent users from depending on

interfaces that are not implemented, and to signal

that something has gone wrong in construction.#2047

Including the why in addition to the what, and potentially some extra info (an issue number, a link to documentation, etc.) in the commit can speed up future work in the area.

Rebasing, Fixup Commits, and More#

Branches allow you to do some other interesting things, like amending commits, reordering commits, and the such without messing up others’ work. Have you ever had to write a commit that says something like “Fix the tests”, “Fix comment typo” or “Fix the build”?

Fixup commits and rebasing may help you keep your history cleaner, focused on what changes you are actually making (the features being added, the bugs being fixed, etc.). To start, figure out the commit hash that you want to change:

git commit --fixup=[commit hash with issue]Then later, you can run this:

git rebase --autosquash [first commit on branch]^Which will squash the fixup commit into the previous commit, and update the

following commits to have the new commit as their parent. Because this rewrites

history, this is better done on a branch than on main where someone else may

have already pulled changes.

Automated Tests#

I feel like I have beat this horse into the ground. Write tests. They’re a smaller up-front investment for a longer-term benefit of not being able to break things as easily.

Incremental Changes#

Not every issue needs to be solved in one pull request. If you can break things up into smaller changes, both you and your collaborators will have a better time. Smaller changes are easier to review, easier to write tests for, and easier to merge. There’s a balance to find here between PRs and commits as well, but incremental changes are something worth considering as you work with other engineers.

Code Reviews#

Unless you are working alone (and even then, I’m happy to review PRs if you want), you should have another human review your code as well. It’s a fantastic way to make sure that your code can be understood, and fits in both of your mental models of your larger system.

GitHub Actions#

GitHub actions is a CI pipeline, and generally good for running automation on pull requests without needing to set up other automation. Other git providers have similar pipelines as well, or you can use a third party pipeline like Jenkins.

Here is the workflow I am using for my project. It runs with a database, and runs my unit tests, formatter, linting, etc. to make sure that it’s deployed.

.github/workflows/tests.yml

name: Build and Deploy (Preview)

on: push: branches: [next] pull_request: branches: [main, next]

jobs: build: name: Build and Run Tests (Preview) runs-on: ubuntu-latest container: image: ubuntu services: postgres: image: postgres env: POSTGRES_USER: postgres POSTGRES_PASSWORD: postgres options: >- --health-cmd pg_isready --health-interval 10s --health-timeout 5s --health-retries 5 env: POSTGRES_PRISMA_URL: postgresql://postgres:postgres@postgres:5432/postgres POSTGRES_URL_NON_POOLING: postgresql://postgres:postgres@postgres:5432/postgres CI: true steps: - uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Install Node.js uses: actions/setup-node@v3 with: node-version: 18

- name: Install Vercel CLI run: npm install --global vercel@latest - name: Pull Vercel Environment Information run: vercel pull --yes --environment=preview --token=${{ secrets.VERCEL_TOKEN }}

- uses: pnpm/action-setup@v2 with: version: 8 run_install: false

- name: Get pnpm store directory shell: bash run: | echo "STORE_PATH=$(pnpm store path --silent)" >> $GITHUB_ENV

- uses: actions/cache@v3 name: Setup pnpm cache with: path: ${{ env.STORE_PATH }} key: ${{ runner.os }}-pnpm-store-${{ hashFiles('**/pnpm-lock.yaml') }} restore-keys: | ${{ runner.os }}-pnpm-store

- name: Install dependencies run: pnpm install

- name: Generate database run: pnpm run db:generate

- name: Lint run: pnpm lint

- name: Check Format run: pnpm format

- name: Generate database run: pnpm run db:generate

- name: Build run: pnpm build

- name: Run migrations run: pnpm db:deploy

- name: Run unit tests run: pnpm testContinuous Delivery#

Continuous delivery means automatically releasing your code to your users. Some teams find this fine to do as soon as it is merged and tested. If your app is much more client-focused (and heavy), it might make sense to keep it cached, and release once or twice a day to reduce the amount of bandwidth users need to use loading the code.

On Vercel, this is automatic. When you push to your main branch, it gets deployed to production so long as the build passes. I found that the double build isn’t as useful, so I deploy as a part of my GitHub Actions build process here, but you can do what works best for you.

Some other options:

- Build a container on your CI pipeline, deploy it to a container registry (like Google Cloud, or AWS), and trigger a deploy from the container registry.

- SSH into your production server, trigger a git pull, and restart the server.

Staging Deploys#

I’ve mentioned this in the past; having a safe environment to test changes that mirrors your production environment can save you a lot of headache in the future. I recommend a workflow that looks like this:

- Create a pull request to a

nextordevelopbranch that runs tests, format, etc. - Do code review on the pull request

- Merge to

nextordevelop - Automatically deploy that to your staging environment

- Check the logs for database / build issues (or better yet, create alerts for those things that will notify you if things fail)

- Run tests against that environment (optional)

- Check that your flow works in that environment

- Merge to

main

Homework#

- Do a fixup commit